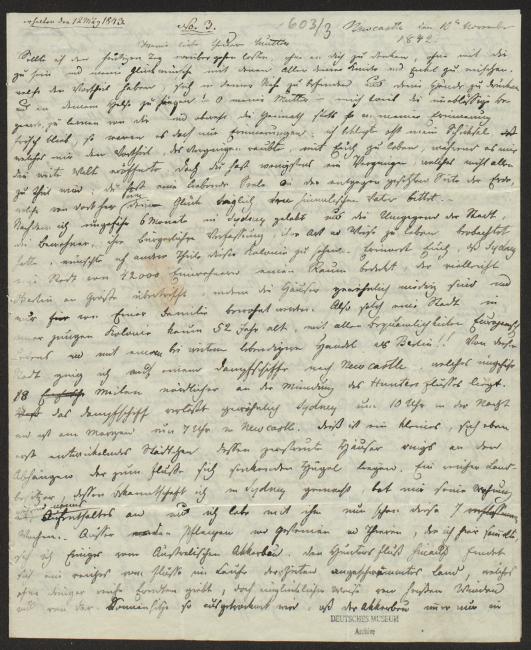

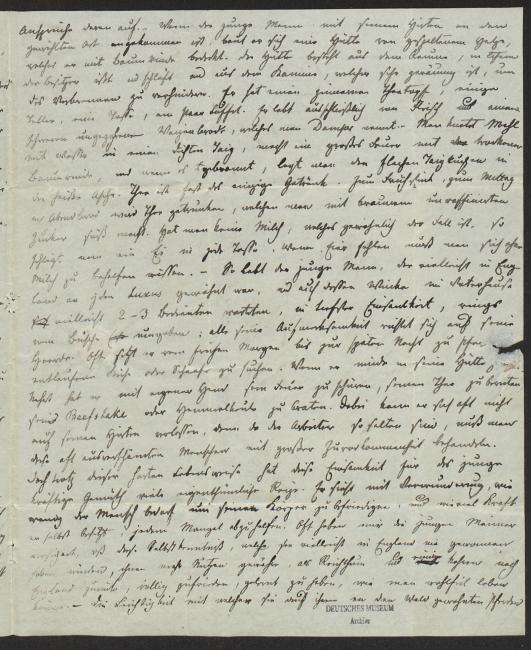

Letter to his mother, Charlotte Sophie Leichhardt, Newcastle (10 November 1842)

Newcastle, 10 November 1842

My dear beloved mother,

How can I let the today pass without thinking of you, without being with you and adding my well-wishes to those of all of your children and grandchildren who have the advantage of living near you and can shake your hand and hug you! — O mother—the incessant appetite to learn drove me away from you and although my home remained continually present in my memories, they were only memories after all; I often lamented my fate which robbed me of the benefit, of the joy of living with you, although it opened the wide world for me. Yet at the very least you can take delight in one thing that not everyone enjoys; you have a loving soul on the other side of the earth which thence daily prays for your happiness to our heavenly Father. —

After I had lived in Sydney for about six months and had studied the city’s surroundings, inhabitants, its state of public affairs, and its way of life, I longed to see other parts of this colony. Remember that Sydney, a city of 42,000 inhabitants, covers a space that is perhaps bigger than Berlin due to the fact that the houses are customarily low-ceilinged and only inhabited by one family. Well now, [imagine] such a city in a young colony scarcely 52 years old, with all the comforts of European life and much livelier trade than in Berlin!! From this city I took a steamship to Newcastle, which is situated about 18 miles to the north, on the mouth of the Hunter River. The steamship typically leaves Sydney at 10 o’clock at night and arrives at Newcastle at 7 o’clock in the morning. This is a small city just beginning to develop, whose scattered houses sit atop the slopes of hills that dip down toward the river. A wealthy landowner, whose acquaintance I made in Sydney, offered me his apartment for the duration of my stay and I have now been living with him for these past seven weeks. Apart from the plants, rocks, and animals that I collected here, I’ve seen something of Australian agriculture. Upstream of the Hunter River there is rich soil that the river has deposited over the years, which yields rich harvests without the aid of fertilizers; yet unfortunately hot winds and the heat of the sun dry it out so much that farms can only count on a good harvest one year in three.

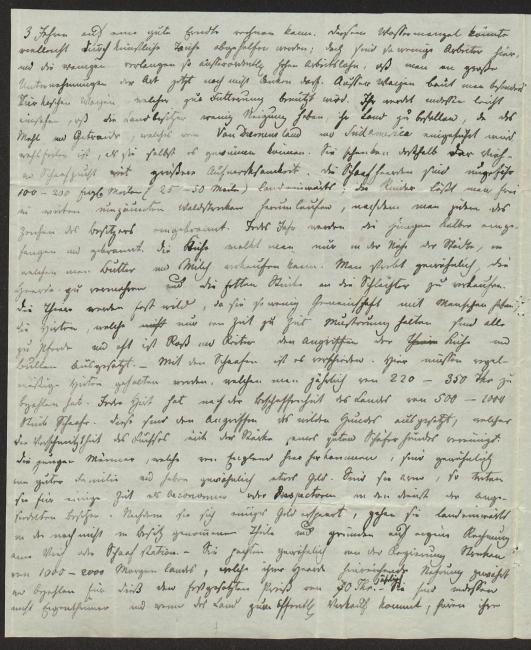

Artificial lakes could perhaps alleviate this water shortage; yet there are such few laborers here, and these few demand such extraordinarily high wages, that larger undertakings of this kind are out of the question for now. Apart from wheat, for the most part they grow maize, which is used as animal feed. You will easily recognize that landowners are hardly inclined to cultivate their land since the flour and grain that is imported from Van Diemen’s Land and South America is less expensive than what they can produce themselves. They therefore concentrate much more on livestock and sheep farming. The flocks of sheep are approximately 100–200 English miles (25–50 German miles) inland; cattle are allowed to roam freely in wide, unfenced swaths of woodland after each has been branded with its owner’s mark. Every year the young calves are caught and branded. Cows are milked only in the vicinity of cities in which butter and milk can be sold. Generally speaking, farmers try to increase herd size and sell the fat stock to the butchers. The animals are almost feral since they have so little interaction with humans. The herdsmen, who only make their rounds to examine the herds from time to time, are all mounted on horseback, and frequently horse and rider are subjected to attacks by the cows and bulls. — It’s different when it comes to the sheep. For this, regular shepherds have to be employed, who must be paid 220–350 dollars in annual wages. Depending on the terrain, every shepherd is responsible for 500–1000 sheep. These are vulnerable to attacks by dingos, which combine the cunning of the fox with the strength of a good sheepdog. The young men who arrive here from England typically come from good families and by and large possess some means. If they are poor, they enter into the services of established settlers for a little while, as accountants or inspectors. After they have saved up some money they move further inland to the as-of-yet unsettled parts and use their own capital to establish a cattle or a sheep farm. As a rule they lease between 1000 and 2000 morgen of land from the government, which provides their herd with ample grazing ground, and pay the fixed price of [50?] dollars annually. — They do not own the land, however, and when it is sold at public auction their claims

on it cease. Once the young man and his shepherd have arrived at the selected spot, he builds himself a hut made of split timber, which he roofs with tree bark. The hut consists of a room in which the settler eats and sleeps and of a fireplace, which is very spacious so as to prevent a conflagration. He has a tin teapot, a few plates, one cup, a couple of spoons. He subsists entirely on meat and a heavy, unleavened wheat-based bread called “damper.” — Flour is mixed with water to produce a dense dough, a huge fire is made with dried tree bark, and once the fire has died down the flattened dough is put into the hot ashes. Tea is almost the only available beverage. For breakfast, lunch, and dinner one drinks tea, sweetened with brown unrefined sugar. If there is no milk to be had, which is usually the case, a beaten egg is added to every cup. If eggs are absent, one has to make do without dairy. — Thus the young man, who perhaps was accustomed to every luxury in England, and on whom perhaps 2 – servants waited hand and foot in his father’s house, lives in profound solitude, surrounded by the bush on all sides; all of his attention is given to his herd. He is frequently in the saddle from early dawn until late at night, seeking escaped cattle or sheep. When he returns to his hut bone-tired, he has to stoke up the fire himself, has to make his tea, and cook his beefsteak or mutton chop. Often he cannot depend on his shepherd for help, because laborers are so rare that these impudent people often have to be treated with the utmost courtesy. Yet despite this hard way of life, this solitude has a particular appeal to a young, robust mind. He is astonished to find how little a person requires to satisfy his bodily demands and how much power he himself has to address any need. The young men often assured me that this self-knowledge, which they perhaps never would have acquired in England, is of more use to them than any riches, and some return to England completely content just with having learned how to live inexpensively. — The ease with which they roam the bush

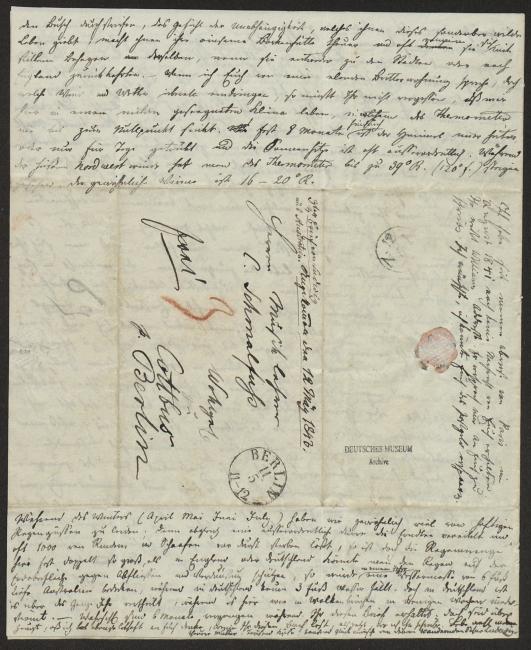

atop their horses, which are used to wooded areas, the feeling of independence with which this peculiar, this wild life instills in them renders their solitary bark-covered hut dear to them and they often think back to it with quiet contentment after they have returned either to the cities or to England. If I paint a picture of a miserable shack exposed to wind and the elements on all sides then you must keep in mind that we live in a blessedly mild climate here, in which the thermometer never drops below freezing. For almost 8 months straight the sky is continually bright blue, or only cloudy for a few days, and the heat of the sun is frequently extreme. During the hot northwestern winds, the thermometer has been seen to climb up to 39° R (120° F.). Normally it is 16–20° R.

During the winter (April, May, June, July) we usually suffer under heavy downpours; even though extreme drought blights the harvest and often causes thousands of cattle and sheep to die of thirst, the amount of rainfall here is almost twice as high as it is in England or Germany. If the rain falling on the soil could be prevented from running off or evaporating, within one year a mass of water 6 feet deep would cover Australia, whereas hardly 3 feet of water fall on Germany. Yet in Germany this amount is spread out over the entire year, whereas here it pours down in torrents within the space of a few weeks. — When you receive this letter, 6 months will presumably have passed; yet be sure that I think of you as fervently when you read this letter as I do now while I am composing it. Farewell, beloved mother. A thousand kisses, a thousand well-wishes from

Your wandering son,

Ludwig

[P.S.] I have not received a message from you since my departure from Paris in August 1841. You know William’s address. He promised me to write to you. I wish I could spare you the expense of postage.

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/3.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.