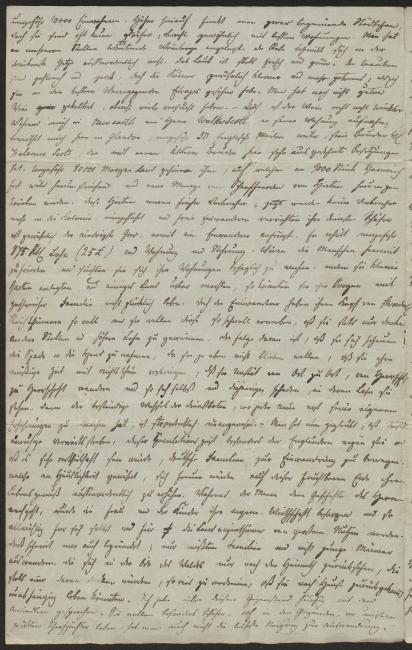

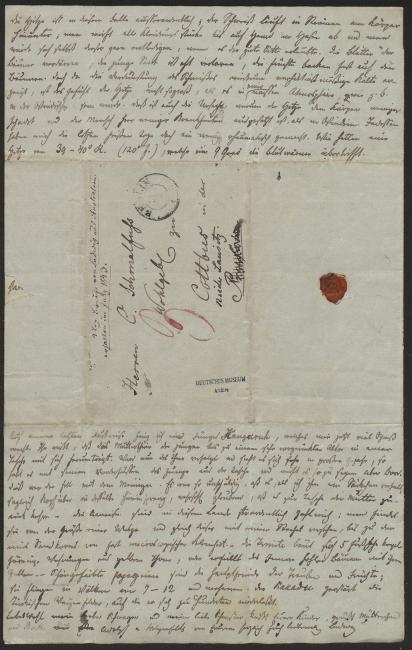

Letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, Glendon (16 January 1843)

Glendon, 16 January 1843

My dearest brother-in-law,

I received your letter of condolence at the beginning of December 1842. I cannot tell you how much the death of our dear sister Mathilde pained me. Yet I thank you for the gentle and diplomatic way in which you broke the terrible news to me. — You filled my mind with a whole host of memories of home; with tears in my eyes I accompanied you step by step on the well-travelled road from Cottbus to Trebatsch; I was so filled with melancholy about how everything has changed that the last, grievous message simply made the bucket overflow and I wallowed freely in my grief. Yet on the other hand I was glad to know that Adolph has taken possession of our father’s property. I was happy that Barth has extended a helping hand to him in this and that, by the same token, our dear mother can finally move into the residence reserved for her after waiting so long. May Adolph only be fortunate in choosing a wife who will treat mother well, so that her remaining days will not be marred by an unkind daughter-in-law.

After I had lived in Newcastle for about 8 weeks and from there had undertaken excursions in all directions, I bought a horse and thus, excellently fitted out, rode up the Hunter River. Whenever I encountered steeper hills I left my horse on good pastures and climbed the hills to examine their formation and the rocks of which they consist. A few shirts, a tea kettle, 1 £ of tea, and 2 £ of brown sugar were all I brought to sustain me. The settlers, who usually accorded me a friendly welcome, supplied me with damper, a kind of bread made of unleavened dough which is baked in hot ashes, and meat, and once in a while milk and eggs. In case I had to sleep under the open sky in the bush I carried a woolen blanket, in which I wrapped myself and then laid down beneath a tree. I camped out in this manner along the seashore, where the roar of waves lulled me to sleep, and within isolated woodlands, in which kangaroos grazed around me. — People wandering the forests of New Holland have nothing to fear from wild animals; the largest carnivorous animals are wild dogs the size of jackals which, although they do great harm to sheep, do not dare attack humans. The solitude of the forest, in the quiet of night beneath a brightly sparkling firmament, leaves an extremely deep impression on a lonely traveler — and I will never forget some of the nights of this sort. Yet the forest does alternate with open, cultivated regions, as is the case at home. Now and then in the outback, one finds close to a settler’s hut a small area cleared of trees for growing a little wheat or maize. Yet for the most part the settlers are busy with livestock breeding or sheep farming and buy their flour in town. The drought has lasted an extremely long time; the highly-praised banks of the Hunter River had barely enough grass to nourish my horse scantily. The entire region appeared as if it had been scorched. About 5 miles from Newcastle there is Maitland, a much more important city of

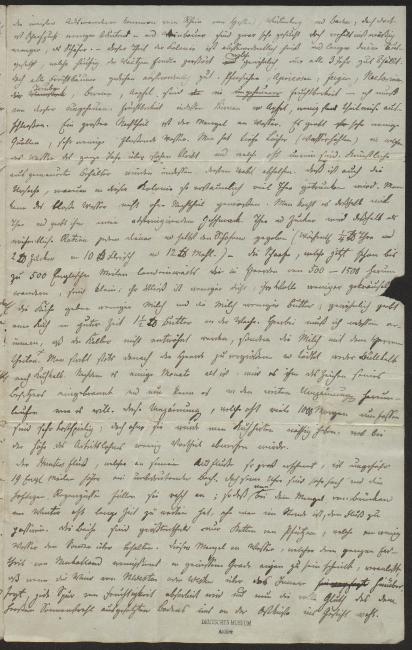

about 10,000 inhabitants. Although the beginnings of cities can be found higher up, they frequently hardly even qualify as villages, albeit with better dwellings. Considerable vineyards have been established in several places. The vines do exceedingly well in the most oppressive of heats. The leaves are always fresh and green, the grapes are numerous and large, while the seeds are usually smaller and further apart than I have seen them in the best wine regions of Europe. A great wine has not yet been pressed, although many have tried. — Yet the wine is quite drinkable. While a Mr. Walker Scott welcomed me into his home in Newcastle, I am entertained here in Glendon, about 50 English miles away, by his brother Mr. Helenus Scott, who owns vast property together with an older brother. Approximately 80,000 morgen of land belong to him, on which 9000 head of cattle run more or less rampant, and a great many flocks of sheep are driven about by shepherds. In the past, many shepherds were convicts; nowadays convicts are no longer brought to the colony and free immigrants do their jobs. Shepherd is usually the lowest rank at which an immigrant begins. He receives a salary of about 175 Rtl. (25 £) as well as room and board. If people would be content with this and try to make their settlements comfortable by planting small gardens and preparing a bit of land for farming, then they could live quite happily and free of worries with large families. Yet the immigrants’ minds are so filled with thoughts of great riches, which they want to acquire as quickly as possible, that they think of nothing except how to secure other employment and higher wages. Consequently, they are reluctant to pick up a spade because they do not plan on staying as it is, so that they spend their free time doing nothing and migrate from place to place and master to master, and in this way harm themselves and their employers. For the constant change of servants is extremely bothersome, since each new person has to acquire experience. — This anxious striving forward, this fondness for speculation, has been perceived as a peculiar trait specific to the English and that it would be very advantageous to convince German families to immigrate, who, used to domesticity as they are, would be eager to greatly increase their standard of living on this fertile soil. While the man would tend to his master’s affairs, his wife and children would look after the family business and in this way would gradually benefit both themselves and the landowners. I recognize the logic of this; yet whole families must emigrate, not just young men who long for home amidst the bleak forest, and who would always think only of making as much money as would enable them to return home as persons of independent means. I have frequently spoken with settlers about this matter. They are specifically seeking shepherds: yet in the regions where our best sheep farmers live there is no one who is even the slightest bit inclined to emigrate.

Most emigrants come from the Rhine region, from Hesse, Würtenberg [sic] and Baden; yet sheep farming plays less of a role there — and although vintners are much sought-after, they are relatively speaking less in demand than shepherds. — This part of the colony is extremely hot and subject to long droughts, which frequently destroy the wheat harvest that usually only turns out well 1 year in 3 to begin with. Yet all fruit trees thrive exceptionally well. The fertility of peaches, apricots, figs, nectarines, grapes, pears, apples is immense — although I have to at least partially exclude pears and apples when it comes to this incredible fertility. The lack of water is a big disadvantage. There are very few springs, very little running water. There are deep holes (waterholes) in which water stands year-round, and which are often brackish. However, artificially constructed brick containers would help redress this ill. This is also the reason why such astounding quantities of tea are consumed in this colony. Plain water cannot be enjoyed without harm. It is therefore boiled with tea and acquires an astringent taste. Every servant and even the shepherds therefore receives a weekly ration of tea and sugar (¼ lb of tea and 2 lb of sugar and 10 lb of meat and 12 lb of flour per week) — The sheep, which already roam up to 500 English miles inland in flocks of 500 to 1500, are small; their fleece is less thick, their wool less curly; cows produce less milk and the milk makes less butter; a cow commonly yields 1½ lb of butter per week when times are good. With regard to this point I must highlight, however, that calves are not weaned but share their master’s milk. Everyone is constantly striving to increase the size of the herds and neither male nor female calves are killed. When they are a few months old, they are branded with the seal of their owner and can then run around the vast enclosures to their heart’s content. These enclosures, which frequently encompass 1000 morgen, are very expensive; yet without them cowherds would become a necessity and their high salaries would leave little in the way of profit.

The Hunter River, which appears so enormous at its mouth, turns into an insignificant rivulet about 19 English miles higher up. Yet its banks are very steep and the torrential rains quickly fill it; the lack of bridges therefore means that in the winter one has to wait long periods of time before crossing the river becomes possible. For the most part, the rivulets are simply chains of puddles that retain a bit of water in the summertime. This lack of water, which seems to afflict the entire continent of New Holland at least to some degree, causes every trace of moisture to be absorbed when winds from the northwest or west sweep across the interior, and means that those of us on the east coast get the full heat of the earth exposed to the sun blowing on our faces.

When this happens, the heat is unbearable; sweat runs down one’s body in streams; all items of clothing except for shirt and pants are discarded and one would gladly take off those as well if decency would permit. Tree leaves desiccate, young crops are often lost, fruits almost bake on the trees. Yet since evaporating sweat in turn has a relative cooling effect, the heat is not felt to be as great as it would be in a wet climate, as prevails in the East Indies, for example. This is also the reason why the heat is less harmful to the body and people here suffer from fewer diseases than in the East Indies. The recent hot days have nonetheless made me a bit rheumatic. We had hot temperatures of 39–40° R (120° F), which exceeds blood heat by 9 degrees.

During my last journey on foot I caught a young kangaroo, which now affords much amusement. You know that the mother carries the young in a pouch until they are quite advanced in age. Now, if the animal is being chased and finds itself in great danger, it lifts the young one out of the pouch with its front legs and throws it overboard, so to speak. This is what happened to mine. It was so innocent that it jumped head-first into a bag which I held in front of it, probably believing that it was returning to its mother’s pouch. — Ants are extremely numerous in this country; you can find some as big as wasps, endowed with a similar stinger, while others are almost microscopically small, only the size of a grain of sand. — Termites construct cone-shaped dwellings of yellow clay that reach heights of 5 feet, or fill hollow trees with their cells — Magnificently colored parakeets are the main enemies of grapes and fruit; they fly around in flocks of 7–12, or even more. The cockatoos destroy fields of maize, on which they land by the hundreds.

Farewell my dear brother-in-law and my dear sister, give your children a kiss from me, and convey my greetings to mother and the Barths, Adolph and the Hilgenfelds

Most affectionately,

your Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/4.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.