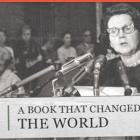

Legacy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring

For me, personally, Silent Spring had a profound impact. It was one of the books we read at home at my mother’s insistence and then discussed around the dinner table… . Rachel Carson was one of the reasons why I became so conscious of the environment and so involved with environmental issues. Her example inspired me to write Earth in the Balance… . Her picture hangs on my office wall among those of political leaders… . Carson has had as much or more effect on me than any of them, and perhaps than all of them together.

—Vice President Al Gore, “Introduction,” Silent Spring (1994 ed.), xiii

By any measure, Silent Spring succeeded beyond anyone’s imagining. By the end of the twentieth century, it took its place on lists of the best books of the century or even of all time. Random House’s Modern Library released a much-talked-about list of the 100 Best Nonfiction books of the twentieth century, on which Carson’s book was ranked #5. Discover Magazine put Silent Spring on its “25 Greatest Science Books of All Time” in 2006. Britain’s Guardian newspaper in 2010 listed it among the “Fifty Books to Change the World.” In 2011, Time magazine put it on the All-TIME 100 Nonfiction Books list. Even the conservative National Review listed Silent Spring on its “100 Best Nonfiction Books of the Twentieth Century.”

More immediately, Silent Spring affected government policy. Every one of the toxic chemicals named in the book was either banned or severely restricted in the United States by 1975. Farm chemicals, pest-control chemicals, and household chemicals undergo much greater scrutiny, regulation, and control than before Rachel Carson published the book, and the chemicals allowed are less deadly and used in smaller amounts.

Logo of the USDA Organic program

Logo of the USDA Organic program

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Logo of the National Organic program

Logo of the National Organic program

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

In a broader sense and the longer term, Silent Spring helped create a change of attitude. It called into question a major item of faith in the twentieth century, the authority of scientific experts. The public had trusted such experts to exert greater control over nature, down even to the atom whose power was made to seem so miraculous, and make a happier, healthier, wealthier society. Carson showed how experts trusted their own creations too greatly and how they themselves were implicated in a vast complex of private and public interests designed to produce profits for chemical manufacturers and the growing agribusiness sector.

Most importantly Silent Spring launched the modern global environmental movement. The ecological interconnections between nature and human society that it described went far beyond the limited concerns of the conservation movement about conserving soils, forests, water, and other natural resources. A generation of Americans found their perspectives widened and their activism inspired by Carson’s powerful work. Although never such a key text in environmental movements outside the United States, Silent Spring did play a role in creating an environmental awareness. It remains in print in many languages, after fifty years still inspiring readers across the globe.

No better evidence of Carson’s significance exists than the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. The decision in 2009 to name an international center for scholarly study after Carson acknowledged the prominence and respect she still commands around the world and also recognized the power her writing has had to move people and bring about change.

The European Organic seal

The European Organic seal

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The Brasil Organico seal

The Brasil Organico seal

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The natural and organic foods movement was small and ridiculed in 1962. In the decades to come, the movement grew until even large supermarket chains and Walmart stores now carry organic food. Carson’s concerns about dangerous substances in food gradually became mainstream concerns. Organic foods constitute a large and growing sector of today’s agricultural production.

Nevertheless, the issues raised in Silent Spring continue to haunt the contemporary world. Worry about chemicals in water and food has expanded beyond those used in agriculture. In the 1990s, concern grew about endocrine disruptors, which are otherwise harmless substances that mimic hormones and disrupt health. In 2007, questions were raised about bisphenol A (BPA), a compound released by certain plastics into food and by many treated cans into canned food. Of particular concern was BPA released by plastic baby bottles. Canada, the European Union, Japan and the United States immediately acted to restrict exposure to BPA, especially in baby bottles.

The increase of endocrine disruptors in food and water has raised suspicions that they are responsible for a multitude of perplexing new problems: genital deformities in increasing numbers of newborn boys, earlier puberty in girls, declining sperm count in adult males, rising rates of prostate and testicular cancer, and problems in sexual development and reproduction. Other possible health effects include abnormal brain development, obesity, and diabetes.

In addition, endocrine disruptors like BPA enter the environment and disrupt fish and wildlife. Scientists have documented numerous effects. Studies have found male fish with female sex characteristics in the Potomac River, Florida alligators with stunted genitals, and amphibians with extra legs, all due to concentrations of endocrine disruptors in water.

The world today is awash in a sea of chemicals never before seen in nature. No one really knows the long-term effects of these substances, individually or in unpredictable combination, either on human health or on the health of the ecosystems upon which we, and all life, depend. The chemicals are not the same as the ones Carson indicted in Silent Spring, yet they are produced, sold, and used on an unsuspecting public by the same interconnected complex of profit-driven companies and government authorities. Carson’s words in her “Fable for Tomorrow” still apply, as if we lived in the future that she imagined: “No witchcraft, no enemy action” had produced our “stricken world. The people had done it themselves” (Carson 1962, 3).