Through the unknown reaches of Australia

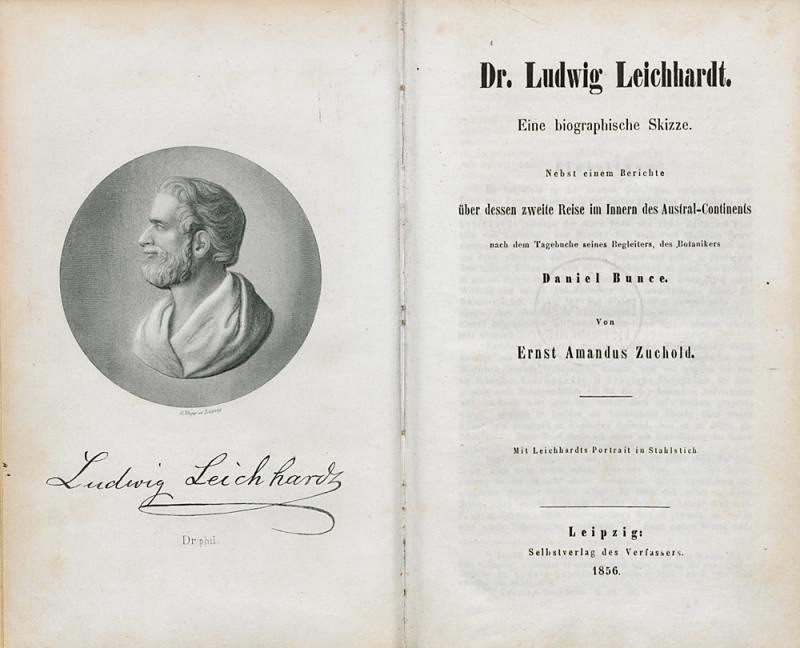

Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt: Eine biographische Skizze by Ernst Amandus Zuchold (1856). Little is known about Leichhardt’s first biographer or his reasons for writing. In 1851 Zuchold had already published a German translation of Leichhardt’s account of the Port Essington expedition.

Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt: Eine biographische Skizze by Ernst Amandus Zuchold (1856). Little is known about Leichhardt’s first biographer or his reasons for writing. In 1851 Zuchold had already published a German translation of Leichhardt’s account of the Port Essington expedition.

Frontispiece and title page of the self-published “biographical sketch” Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt: Eine biographische Skizze: Nebst einem Berichte über dessen zweite Reise im Innern des Austral-Continents nach dem Tagebuche seines Begleiters, des Botanikers Daniel Bunce by Ernst Amandus Zuchold (Leipzig, 1856).

Courtesy of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Signatur Zu 2987.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany License.

Ludwig Leichhardt’s life is inextricably bound with the European exploration of Australia. While the end of his life on his last expedition into the interior of the continent in 1848 remains as mysterious as ever, his biography as a whole is well known. In 1856, Ernst Amandus Zuchold published the first biographical study of Leichhardt’s life in his native Germany. In the 1860s, the German zoologist Gerard Krefft’s biographical sketch chronicled Leichhardt’s life for an Australian audience. He drew upon documents from Leichhardt’s personal possessions, which the explorer had left with a friend before departing on his last journey. By 1854, the friend had given up all hope of Leichhardt’s return and donated Leichhardt’s belongings to the Australian Museum in Sydney, where they were discovered years later by Krefft, who worked as a curator there (Stephens 2007, 195). Since then, in light of changing textual evidence and historical contexts, numerous biographies have revisited the question of Leichhardt’s place in German and Australian history and his suitability as an expedition leader.

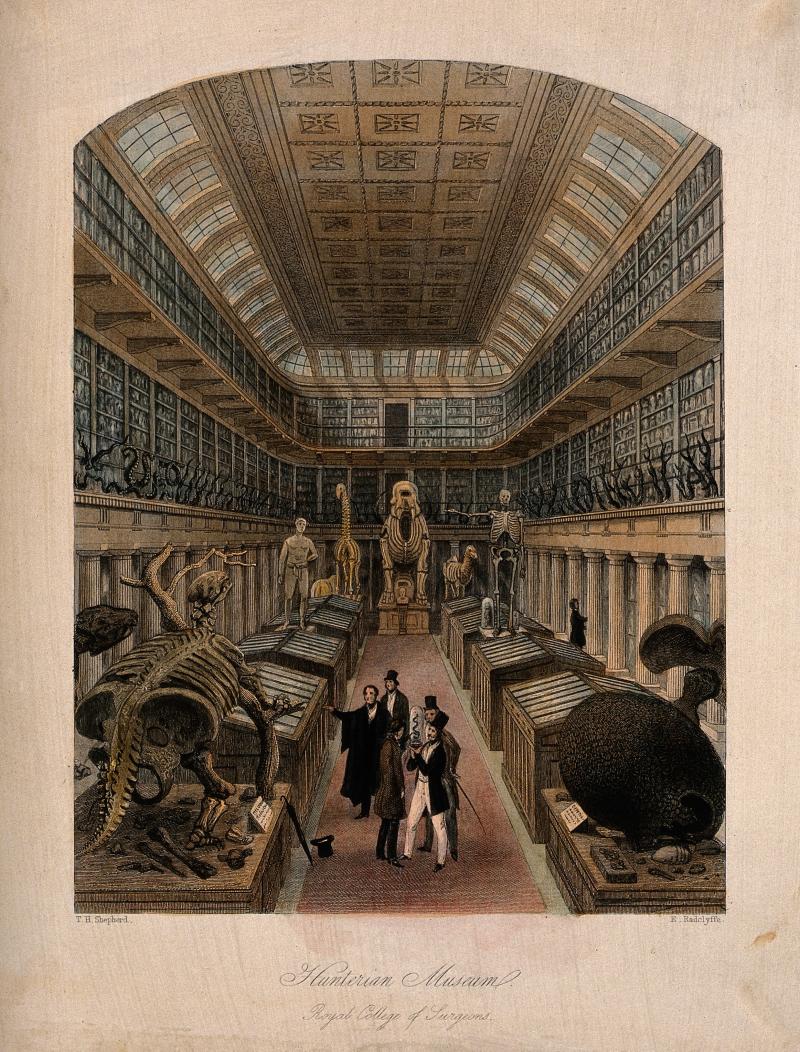

The Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons. Ludwig Leichhardt studied its zoological specimens during his stay in London.

The Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons. Ludwig Leichhardt studied its zoological specimens during his stay in London.

Edward Radclyffe, based on a drawing by T. H. Shepherd, London, early 1840s. Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt was born on 23 October 1813 in the Prussian village of Trebatsch. After graduating from school in Cottbus, he began studying at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin in 1831; in 1833 he transferred to the university in Göttingen for a year. Leichhardt’s interests increasingly focused on the natural sciences and medicine. During his studies he became acquainted with the British Nicholson brothers; an especially close friendship developed with the younger brother, William, who also provided him with financial support. In 1837 Leichhardt left university without graduating and accompanied William to England. Together they prepared themselves for careers as naturalists, undertaking excursions, and studying natural history collections in London. In 1838 they continued their studies at the leading research institutions at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. In fall 1840, the two friends departed on a trip across southern Europe, climbing the volcanic peak of Auvergne, visiting ancient ruins and cultural sites in Italy, and trekking through the Alps. But William withdrew from their plans for a scientific expedition overseas. In October 1841 Leichhardt boarded a ship to Australia alone. He was educated in many aspects of natural history and had contacts with important scholars. He was pursuing his goal of exploring the natural world of the fifth continent.

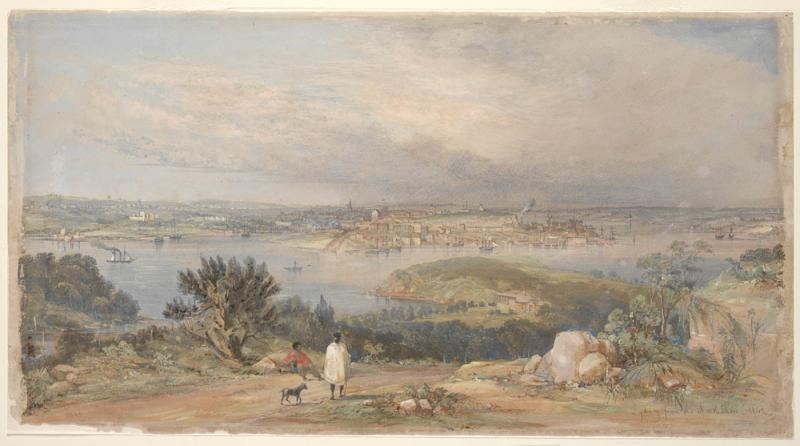

Views of Sydney, from St Leonards, 1842. (Tinted lithograph, with hand colouring by Conrad Martens [1842], Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney).

Views of Sydney, from St Leonards, 1842. (Tinted lithograph, with hand colouring by Conrad Martens [1842], Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney).

Public Domain. Tinted lithograph, with hand coloured by Conrad Martens (1842).

Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.Views of Sydney, from St Leonards, 1842.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Leichhardt arrived in Australia in February 1842 and settled in Sydney. At the time, the interior of the continent was mostly considered unexplored territory, while the British colonies along the coast offered ideal starting points for an expedition. After preliminary field studies in the immediate area, Leichhardt traveled through the colony between September 1842 and May 1844, examining the flora, fauna, and geology from New South Wales to present-day Brisbane. Upon returning to Sydney, he organized his natural history collections, wrote a geological treatise, and began planning an overland expedition from Moreton Bay (the region of present-day Brisbane) to Port Essington (near present-day Darwin). The final expedition party traveled for nearly 15 months, arriving at their destination on 17 December 1845. All but one of the eight men, the bird collector John Gilbert, survived the journey across more than 4,800 kilometers of unexplored wilderness.

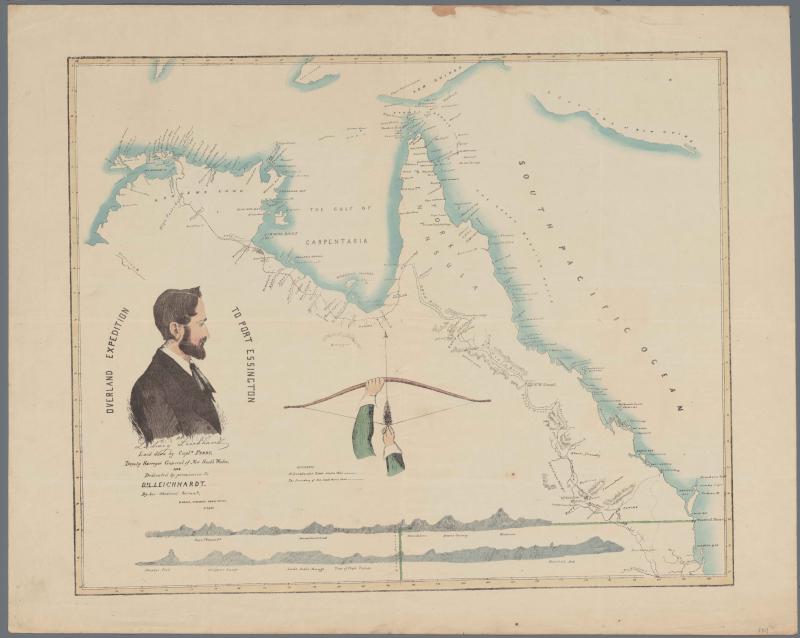

The expedition to Port Essington traveled across unexplored terrain. Leichhardt’s regular measurement of the party’s position aided their travel and was used for mapping the route after their return.

The expedition to Port Essington traveled across unexplored terrain. Leichhardt’s regular measurement of the party’s position aided their travel and was used for mapping the route after their return.

Overland Expedition to Port Essington. Samuel Augustus Perry (1792–1854), Sydney: W. Baker Hibernian Printing Office, 1846. Canberra, National Library of Australia, MAP F 517.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Back in Sydney, Leichhardt and his companions were received with many honors. The journey, which was financed by private money from Sydney businessmen, opened a trade route to the harbor of Port Essington. Even today, landmarks along the route still bear the names of the expedition’s sponsors. Leichhardt’s travel journal, published in 1847, records the characteristics of the regions he passed through, and describes his natural history observations and everyday life on the expedition; it secured his place in history.

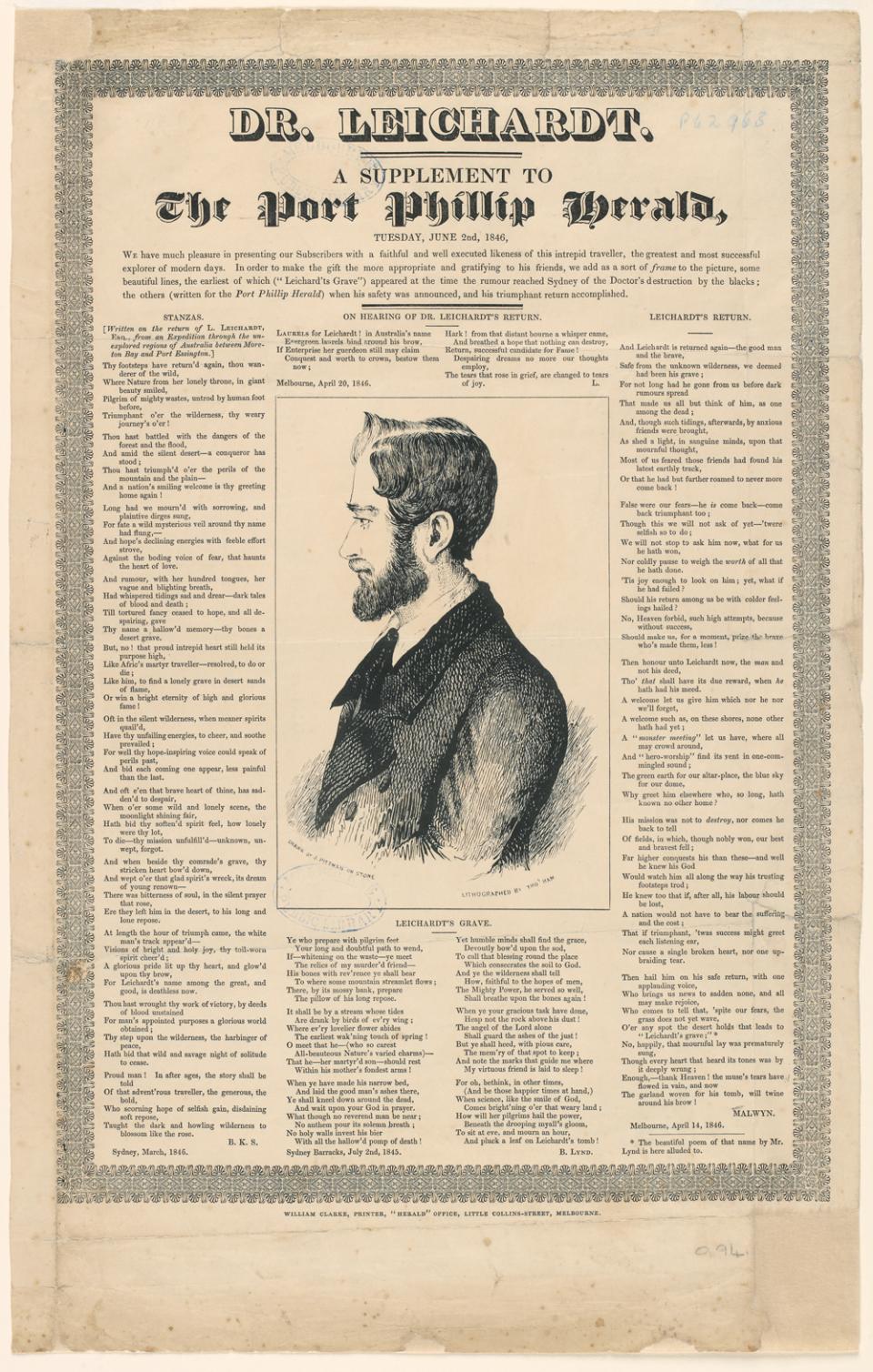

This special supplement in a Melbourne newspaper was published on the occasion of Leichhardt’s return from Port Essington. Poems were composed in his honor, including “Leichhardt’s Grave” by his friend Robert Lynd, who, like everyone else, had already believed Leichhardt to be dead.

This special supplement in a Melbourne newspaper was published on the occasion of Leichhardt’s return from Port Essington. Poems were composed in his honor, including “Leichhardt’s Grave” by his friend Robert Lynd, who, like everyone else, had already believed Leichhardt to be dead.

Lithograph by Thomas Ham (1821–1870), after a drawing by Joseph Pittman (1810–1882) in The Port Phillip Herald, Melbourne, 2.6.1846. Melbourne, State Library of Victoria.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Ludwig Leichhardt had already begun to revise his field notes while still in Port Essington. He received the printed travelogue, which was composed in English and published in London, in February 1848—shortly before he departed on his last journey.

Ludwig Leichhardt had already begun to revise his field notes while still in Port Essington. He received the printed travelogue, which was composed in English and published in London, in February 1848—shortly before he departed on his last journey.

Journal of an overland expedition in Australia from Moreton Bay to Port Essington, a distance of upwards of 3000 miles, during the years, 1844-1845 by Ludwig Leichhardt, London: Boone, 1847.

This book is part of the collection Americana from the library of the University of Michigan. It has been digitized by Google and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Courtesy of the Internet Archive. View image source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In December 1846 Leichhardt set out once more with a new team, this time with the goal of being the first Europeans to traverse Australia from east to west. Their destination was the Swan River Colony, in the region of present-day Perth. After fewer than eight months, adverse weather and declining morale forced the weakened party to turn back. Leichhardt gathered men for a second attempt: after their departure from McPherson’s Station on 5 April 1848, he and his companions—four Europeans and two Aborigines—were never seen again.

Leichhardt mentions his scientific aspirations on multiple occasions, for example in a letter to his sister:

If Nature moves you to such affection, just think how it must move me as I make it my task to uncover her deepest secrets and reveal the laws which make her so majestic, so glorious.

(Letter to Auguste Hilgenfeld, 15 May 1844)

Natural history had become a worldwide pursuit during this time, and Leichhardt had made it his goal “to serve science … by traveling to faraway corners of the globe” (letter to Friedrich August Schmalfuß, 21 October 1847).

His life’s work—contributing to the scientific exploration of the Australian continent—must be considered unfinished. In the colonial backwater Leichhardt never had the resources, nor, in the end, the time, to analyze and interpret his collections and notes; he was able to publish very little. Yet today many museum collections include specimens collected and prepared by Leichhardt—a testimony to his lasting importance for the scientific exploration of the world.