Melbourne: DIY Infrastructure

Map by Nathan Etherington.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Post-World War II Melbourne offers a case study of the causes and consequences of enabling the development of suburbs with low standards of water infrastructure in response to rapid population growth. Service provision by different levels of government lagged behind population growth; as a result, private citizens drew on stocks of “social capital”—the norms, networks, and trust that facilitate cooperation between and within groups—to participate in collaborative problem-solving at a local level.

Melbourne before 1945

Established by Tasmanian squatters in 1835 on land illegally acquired from the Indigenous Wurundjeri population, what is now Melbourne was laid out at a freshwater site on a bank of the Yarra River, around 16 km upstream from its outlet at Hobson’s Bay.

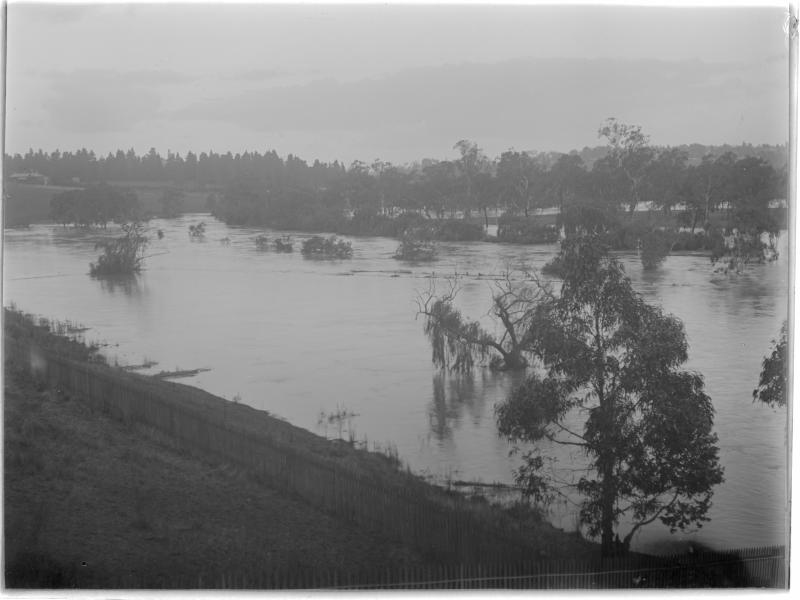

While the Yarra itself is only 233 km in length, its catchment south of the Great Dividing Range extends to over 5000 km², with large floodplains and billabongs (oxbow lakes) along its course holding water after heavy rain and snowmelt. At Melbourne the river reaches an area of flat, swampy ground that is naturally prone to flooding. Gentle hills and river valleys extend to the east and southeast, with a mix of elevated sites and marshy ground extending south along Port Phillip Bay. To the north and west, the soil is heavier, the land generally flat.

Heavy rainfall in April 1901 causes the Yarra to flood its banks. Photograph by Mark James Daniel, 1901.

Heavy rainfall in April 1901 causes the Yarra to flood its banks. Photograph by Mark James Daniel, 1901.

Image courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

While the town center was laid out in a formal grid by surveyor Robert Hoddle after the settlement was officially recognized in 1836, Melbourne’s physical development was driven from the outset by speculators who valued profit over aesthetics.

As the entry port to the Victorian goldfields, Melbourne was the fastest growing city in the world in the early 1850s, with a population that reached 125,000 by 1861. Gold-rush Melbourne was a chaotic boomtown, but safe water was available from 1857. It was drawn from the Yan Yean reservoir, the most ambitious water supply scheme attempted anywhere in the world at the time.

As Mark Twain observed in 1897, “Melbourne spreads around over an immense area of ground.” Like Adelaide and Perth and cities in the western United States and Canada, Melbourne grew by building detached cottages and bungalows close to dispersed docks, factories, and public transport routes to the city center. A preference for single-family houses in a suburban setting was expressed by all classes.

The population of “Marvellous Melbourne” had reached 473,000 by 1891, after growing by 205,000 people in a single decade. Only 15 percent of the metropolitan population lived in the City of Melbourne, with the rest scattered across 19 independent local government areas.

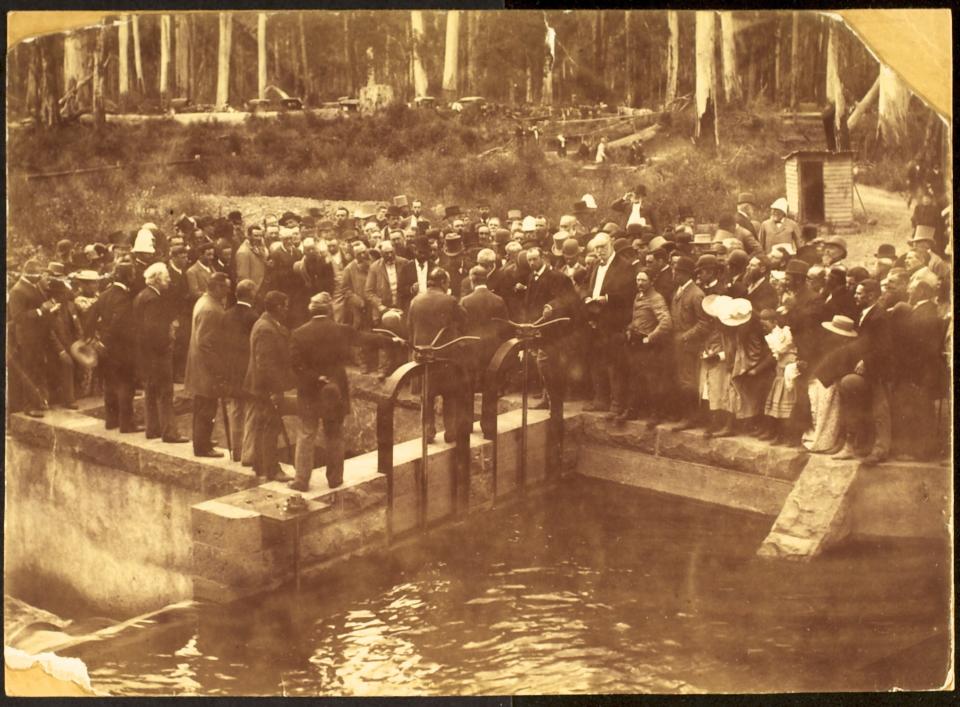

The Watts River Scheme was completed and the water turned on by the Earl of Hopetoun (the Governor), on 18 February 1891. Unknown photographer, 1891.

The Watts River Scheme was completed and the water turned on by the Earl of Hopetoun (the Governor), on 18 February 1891. Unknown photographer, 1891.

© Melbourne Water.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The development of new suburbs depended on the expansion of the publicly owned railway network. In 1891, the colonial government created a statutory authority, the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) to build an underground sewerage system and maintain the water supply. Road construction and drainage was the responsibility of local councils.

When the boom collapsed, Melbourne had enough subdivided land served by railways and tramways to provide new home sites for another half century. The city grew by 460,000 people between 1922 and 1947, with suburban expansion following the existing public transport network. Shopping strips developed at railway stations and tram stops. Beyond easy walking distance, ample subdivided lots remained unoccupied and unpaved roads meandered into farmland.

The average population density of the built-up area declined, as the dominant housing style, the Californian Bungalow, sat across broader lots with space for garages. The extra distance between houses increased per capita infrastructure costs, and the MMBW struggled to keep pace with water and sewerage connections.

Postwar Suburban Pioneers

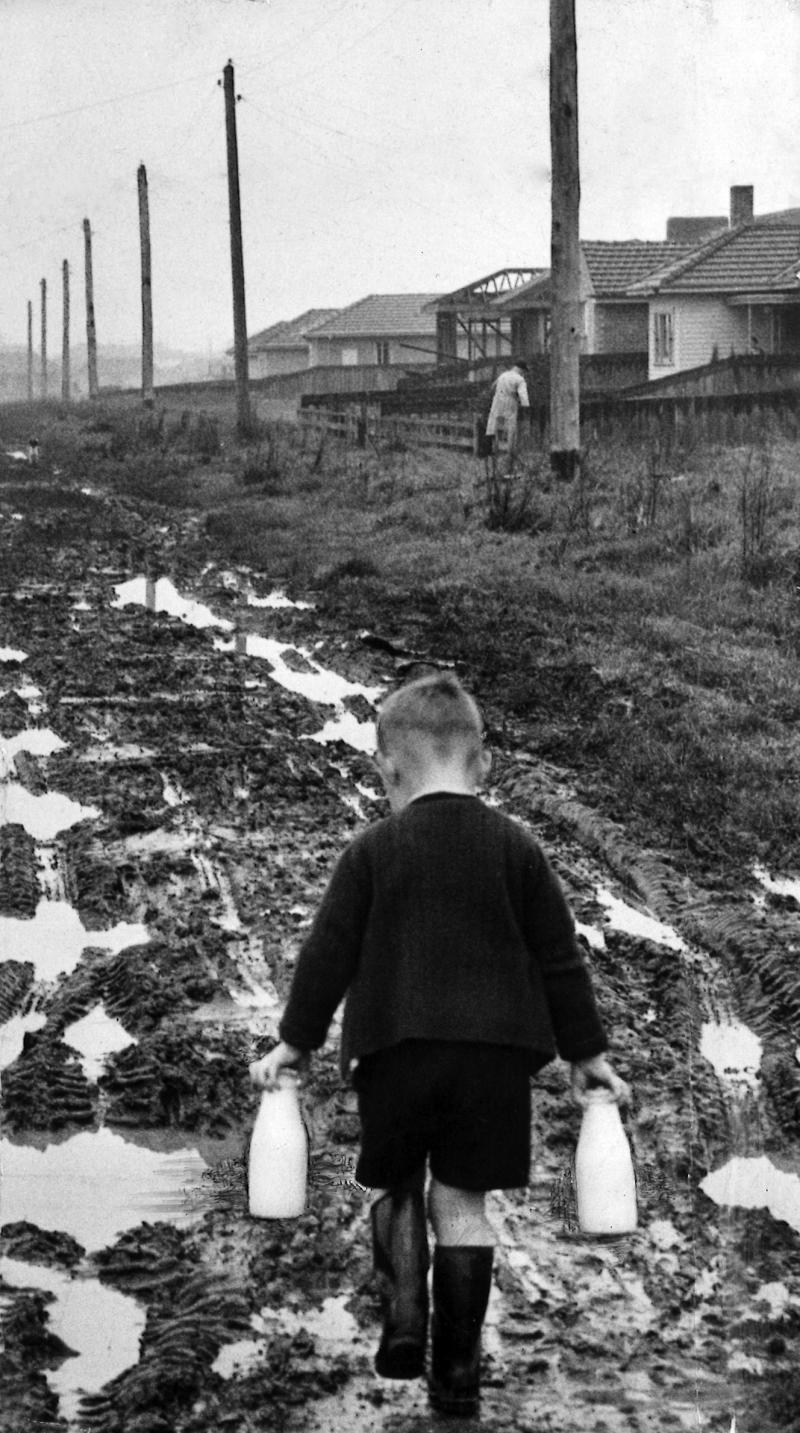

A small boy negotiates a slippery track as he returns home after collecting two pints of milk at the nearest dairy, after milkmen refused to deliver to residents in Birdwood Street, South Oakleigh in Melbourne, Victoria, due to the deplorable state of the roadway. Unknown photographer, 7 June 1949.

A small boy negotiates a slippery track as he returns home after collecting two pints of milk at the nearest dairy, after milkmen refused to deliver to residents in Birdwood Street, South Oakleigh in Melbourne, Victoria, due to the deplorable state of the roadway. Unknown photographer, 7 June 1949.

Photo courtesy of News Limited.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Like other Australian cities, at the end of World War II Melbourne faced a backlog of demand for housing due to deferred consumption and investment. At the 1947 census there were only 877 dwellings for every 1,000 Australian households.

During the postwar economic boom, household expenditure was sustained by almost continuous full employment. With increased aspirations and purchasing power, more Australians bought more houses, cars, and consumer durables. Despite rising construction costs, shortages of qualified building tradespeople, and restricted production of building materials, the city absorbed over one million new inhabitants by 1971, many of them migrants from Europe.

Two-thirds of Melbourne’s population growth between 1947 and 1966 took place in new “greenfield” suburbs. Austere building styles, reduced dimensions of houses, and Commonwealth government subsidies made homeownership feasible for working-class households.

Families continued to aspire to suburban living, and responded to the gap between the cost of buying an established house and their own budget constraints by self-building. Self-building households could either do all of the construction, using family labor and/or that of friends and neighbors; act as site manager, coordinating the various subcontractors in the construction process; or hire a builder and reduce costs by providing “sweat equity” in the form of unskilled labor. Cheap building materials, such as concrete roof tiles, plasterboard, fibro, plywood, compressed fiber board, and metal-framed windows further reduced costs. Throughout the 1950s, around one-third of new Australian houses were owner-built.

Heartbreak Streets and Community Responses

On the suburban frontier, houses, cars, and domestic appliances attested to rising postwar living standards. Amidst this private affluence, outside the houses public squalor prevailed.

Mrs. J. Asbury gives her daughter Barbara a lift across the flooded drain outside her home in Cuthbert Street, Reservoir in Melbourne, Victoria. Photograph by Len Drummond, 1953.

Mrs. J. Asbury gives her daughter Barbara a lift across the flooded drain outside her home in Cuthbert Street, Reservoir in Melbourne, Victoria. Photograph by Len Drummond, 1953.

Photo courtesy of News Limited.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Land prices were low because vacant lots were abundant due to previous subdivision activity. Few services beyond electricity and piped water were provided. The common lot size of quarter of an acre (approximately 1,000 km²) provided room for garages and makeshift bungalows, in which families could live while the main house was being built.

Sewerage provision lagged in the face of high costs and shortages of labor and capital, but lots were large enough to permit the use of septic tanks and pan (pail) toilets. While these solved the immediate problem of disposal, seepage from the septic tanks polluted local waterways.

Local governments generally did not grade roads, let alone metal or pave them, and footpaths, gutters, and stormwater drains were not usually provided.

In the winter of 1955, Melbourne’s Sun newspaper ran a series of reports on the state of the “heartbreak streets”—hundreds of miles of unmade roads in new suburbs. A reporter found that “young couples who have built their homes on the city’s fringes step out of their front gates into mud,” providing further insights with photos and interviews:

Life, the ordinary housewifely shopping outing, which is a pleasure to most women, becomes drudgery. Back home from the shops means … not a cup of tea, but half-an-hour of scraping and washing off mud [from] her pram before she can take it into her house.

In Sunshine where the roads were unmade and there was no running water, Mrs Anita Steigler and her son Ernst along with the family dog set out for home with a bucket of water. Mrs Steigler uses three of these for the family bath. Also pictured is Mrs Urmgard Stanik, who has to carry water home. Unknown photographer, 26 July 1953.

In Sunshine where the roads were unmade and there was no running water, Mrs Anita Steigler and her son Ernst along with the family dog set out for home with a bucket of water. Mrs Steigler uses three of these for the family bath. Also pictured is Mrs Urmgard Stanik, who has to carry water home. Unknown photographer, 26 July 1953.

Photo courtesy of News Limited.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In response, citizen groups, drawing on stocks of social capital, held working bees to improve road surfaces, build footpaths and nature strips (grass verges), and form drains. Women took leading roles in this work, and were active in lobbying local councils and state governments to improve conditions.

In one suburb, groups of housewives built their own roads, wheeling barrows and laying bricks, with their husbands doing the heavier work on the weekends. Volunteers established churches and sports clubs, built community halls, and raised money to support local schools.

While collaborative problem-solving made the “heartbreak suburbs” habitable in the short term, the legacy of poor water infrastructure provision endured for years. The number of Melbourne houses without sewerage stood at 173,000 by 1973, an increase of 56,000 over ten years. To address the problem, the MMBW built the Eastern Treatment Plant, located in the main corridor of suburban growth, which opened in 1975.

Victorian Government planning regulations now required sewerage connection in all new suburbs, and gave local councils the power to compel households to connect if sewerage was available. This stopped any further increase in the number of houses without sewerage, but the MMBW lacked the financial resources to reduce the backlog by building new mains in the outer suburbs.

Unidentified new housing estate in a suburb of Melbourne. Unknown photographer, ca. the 1950s.

Unidentified new housing estate in a suburb of Melbourne. Unknown photographer, ca. the 1950s.

Photo courtesy of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works Collection, H2016.285/17, Pictures Collection, State Library Victoria.

Accessed via State Library Victoria on 13 March 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Soon after coming to power in 1972, the Federal Labor Government established a national sewerage program, grants from which allowed the MMBW to reduce the number of unsewered properties to 88,000 by 1979. After over two decades in which new communities worked to overcome the problems arising from inadequate water infrastructure, the state had resumed responsibility through a mix of regulation and increased funding.

Children ride bicycles near the open drains of Bulli Street, Moorabbin, ca. the 1960s. Unknown photographer, n.d.

Children ride bicycles near the open drains of Bulli Street, Moorabbin, ca. the 1960s. Unknown photographer, n.d.

© City of Kingston.

Image courtesy of the City of Kingston Information and Library Service, L001717.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.