US Government Land Grants: “A pleasure to break the wild prairie”

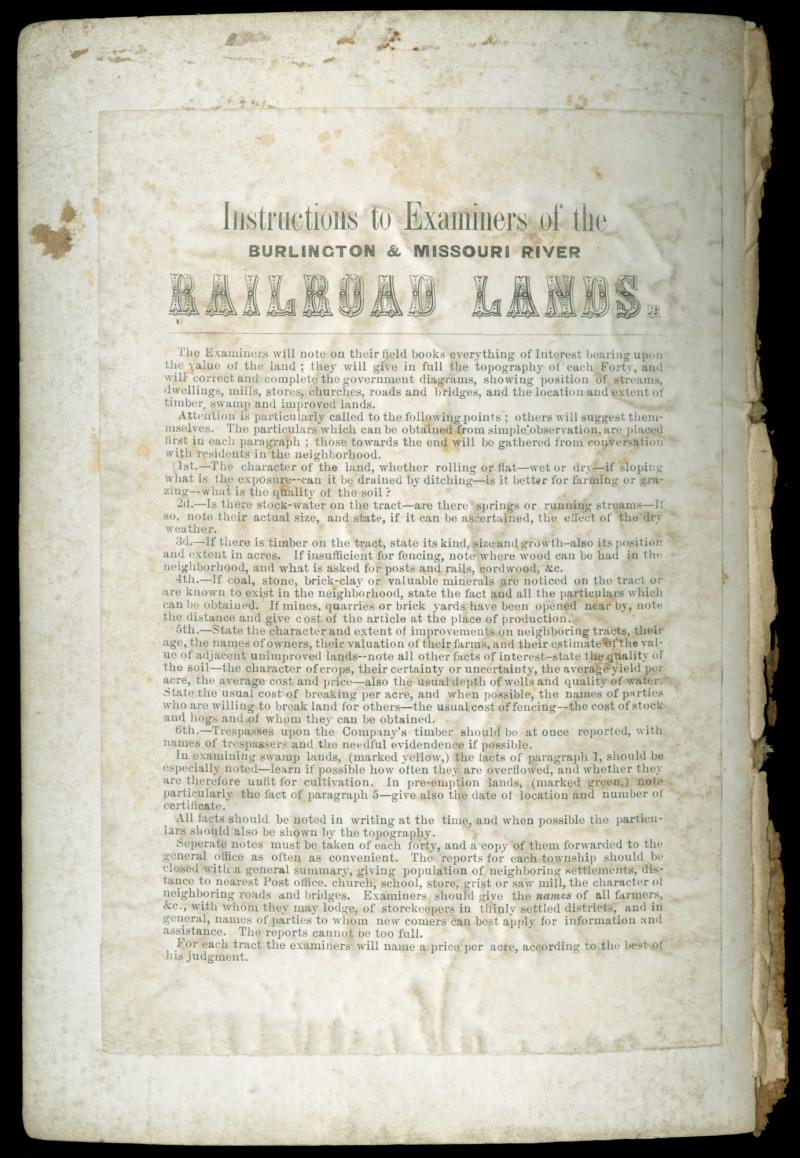

“Instructions to Examiners of the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad Lands,” 1860.

“Instructions to Examiners of the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad Lands,” 1860.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q 755.1, vol.#2.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

As railroads sought to expand westward into sparsely settled regions, they faced a serious dilemma: until the lands around the tracks were settled, passenger and freight traffic would be too small for the railroad company to survive. Furthermore, without rail connections, settlement was bound to continue at a slow and gradual pace. The solution came in 1850 when Congress voted to grant more than two million acres to the state of Illinois to aid the construction of a north-south line. Over the next two decades, more than 129,000,000 acres (about 7% of the continental US) was ceded to eighty railroad companies. The awarding of grants led to sectional conflicts, abuses, and continual arguments over whether or not the grants were too generous to the railroads, but in 1872 Poor’s Manual stated that “no policy ever adopted by this or any other government was more beneficial in its results or had tended so powerfully to the development of our resources by the conversion of vast wastes to all uses of civilized life.” While the land grants may not have been all bad, most scholars take a more negative, or more nuanced, view.

The railroads that would become the Burlington system received more than 3.5 million acres of federal land grants: 600,000 to the Hannibal & St. Joseph in 1852; about 300,000 to the Burlington & Missouri River Rail Road in 1856; and about 2.5 million acres to the B&M RR in Nebraska. The successful land promotion and settlement policies developed by the Hannibal & St. Joseph were later adopted by the Burlington & Missouri River company as they surveyed, built, and actively promoted settlement on their land along the route from Burlington, Iowa, to the Missouri River, and then from the Missouri to Kearney, Nebraska, where they connected to the Union Pacific railway.

The railroad grants helped companies raise the capital they needed to build lines into sparsely settled areas like Nebraska. In exchange, the railways agreed to carry the mail at rates set by Congress and to transport US soldiers and freight without charge. If they failed to complete their lines within a certain time-frame, the lands would revert back to the government. In order for the railroads to develop and sustain profitability, they not only had to sell their lands, but also help to ensure that the settlers’ farms, towns, and businesses along their lines continued to grow and thrive.

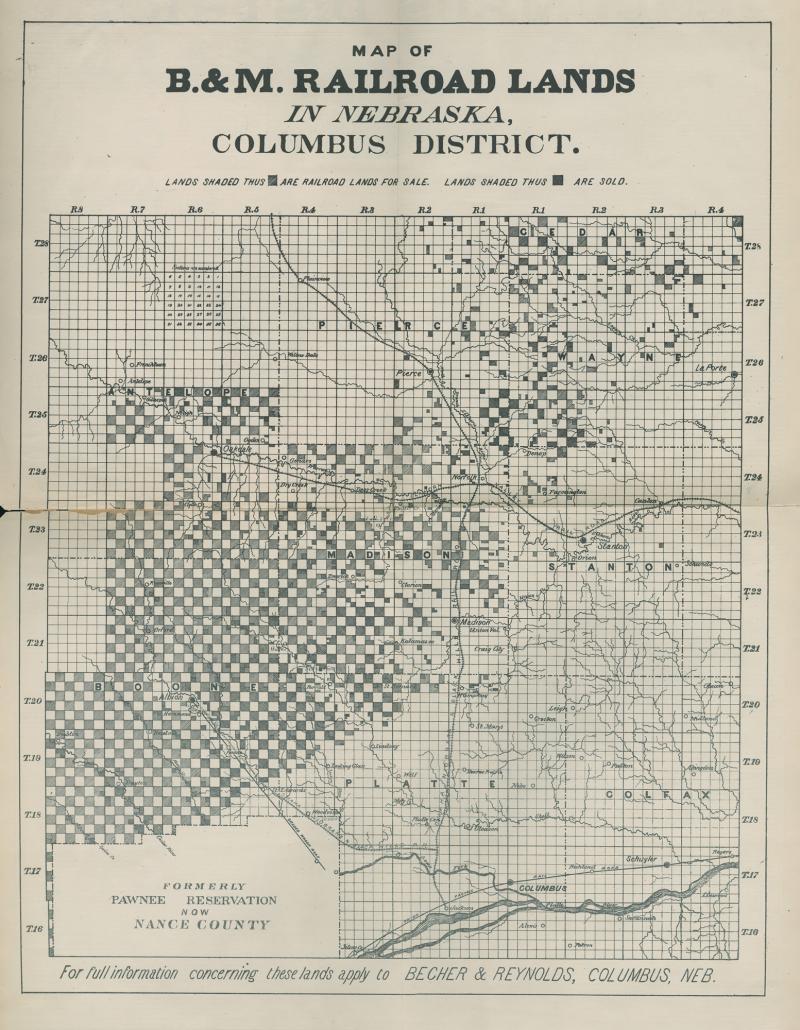

Map of B.&M. Railroad lands in Nebraska, Columbus District, 1880.

Map of B.&M. Railroad lands in Nebraska, Columbus District, 1880.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q 769.8.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Railroad land maps like this one were created to attract settlers and aid them in selecting their land. Typically, the federal government gave the land to the states. The states were to transfer land to the railroads upon the completion of each twenty-mile section of track. The railroad company would then receive alternate sections (a square mile each), six miles on both sides of the track. The price for the alternate sections kept by the government was doubled. If the lands adjacent to the tracks had already been occupied or claimed, the company could make up the full amount by selecting alternate parcels from lieu lands up to fifteen miles on either side of the track. In Nebraska, it was necessary to allow the company to go beyond the 15-mile limit to obtain all of the land to which it was entitled.

The lands had previously been surveyed by the US government, and divided into townships, each containing 36 square mile sections. The numbering system is illustrated in the upper left corner of the map. The lower-left corner of the map shows what had been the Pawnee Reservation.

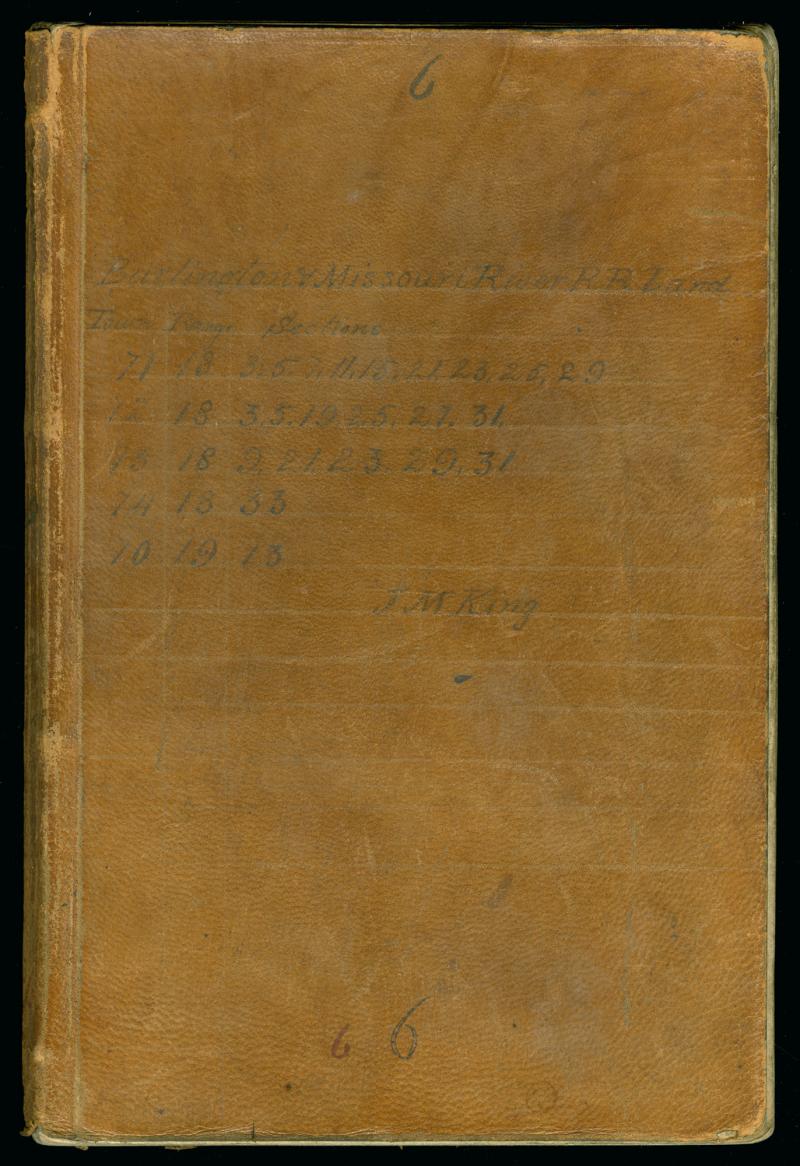

Notes of Railroad Lands Examiner J. M. King, 1860.

Notes of Railroad Lands Examiner J. M. King, 1860.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q 755.1.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Once railroads had established and surveyed the route for their lines, they then commenced a thorough survey of their land grant holdings. The Instructions to Examiners were based on a memo prepared by Berhardt Henn in 1859 that would, according to Overton, form the “basis of all subsequent examinations.” Henn advised that as soon as the General Land Office provided a “clear list” for the grant lands, the company should appoint at least one examiner. The examiners were to be surveyors who could write legibly and knew how to judge the quality of the land. They were provided with a supply of blank books in which they recorded the results of their detailed examination of each 40-acre parcel in their assigned district. The examiners were expected to make a record of everything of use for valuing the land, and describing it for potential buyers. They were to name a price per acre based on their judgment in the field.

The Examiners found problems with the General Land Office surveys, including poorly marked corners. Agents were instructed to talk with neighbors, discover where lodging could be found, and gather names of people with whom potential buyers could correspond.

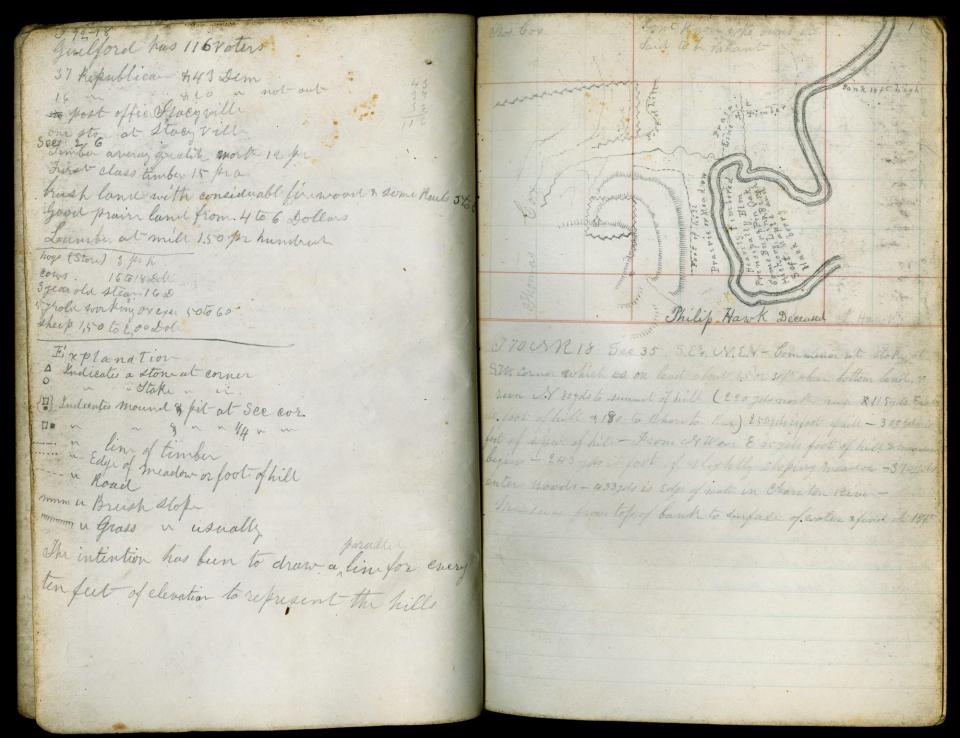

Notes of Railroad Lands Examiner J. M. King, 1860.

Notes of Railroad Lands Examiner J. M. King, 1860.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q “Notes of Railroad Lands Examiner J. M. King,” vol. 6. p. 1v–2r, 755.1.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

These pages from J. M. King’s survey of the company’s Iowa lands in 1860 show how detailed the Examiners books could be. King even drew contour lines for every ten feet of elevation. He listed the number of voters and how many were Republican and Democrat. He showed the neighbors’ holdings, drew in buildings, a fence, and natural features, where the line was between timber and prairie, and even listed the species of trees in a heavily forested area inside a bend of the river.

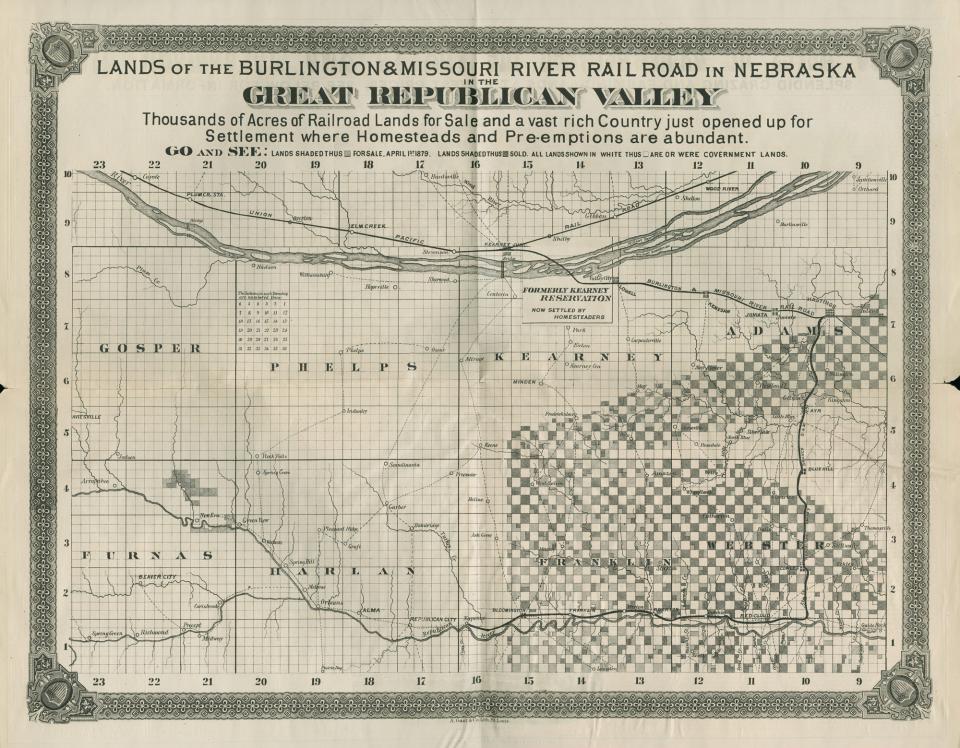

CB&Q map of Great Republican Valley showing lands of the Burlington & Missouri River R.R. in Nebraska.

CB&Q map of Great Republican Valley showing lands of the Burlington & Missouri River R.R. in Nebraska.

Courtesy of Newberry Library. CB&Q 769.8.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Fort Child was established after 1842 to protect the Oregon Trail. It was renamed Fort Kearny in 1848 to honor General Stephen Watts Kearny. The fort was not barricaded and mainly served as a way station and post office for immigrants. Kearney Junction (now just Kearny) was where the B&MR Railroad joined the Union Pacific Railroad. A branch of the B&MR road goes through the Republican Valley. The shaded squares show section granted by the US General Land Office to the B&MR Railroad to sell to settlers to help fund the building of roads. The lighter squares were “for sale, April 1st 1879” suggesting that the map must have been printed before that date. The darker squares represent B&MR lands that have already been sold. Near the bend in the B&MR branch line is the town of Red Cloud, founded in 1871 and named for the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) leader. Oddly enough, in Jules Verne’s 1873 novel, Around the World in Eighty Days, a train under attack by the Sioux stopped and sought help from soldiers at Fort Kearny. Note some of the place names westward and up the Republican River from Red Cloud: Pleasant Ridge, New Era, Freewater, Scandinavia, Green View, Graft. Although Fort Kearny was more a way station than a fort, the succession of fort to settlement symbolizes the passing of the frontier.

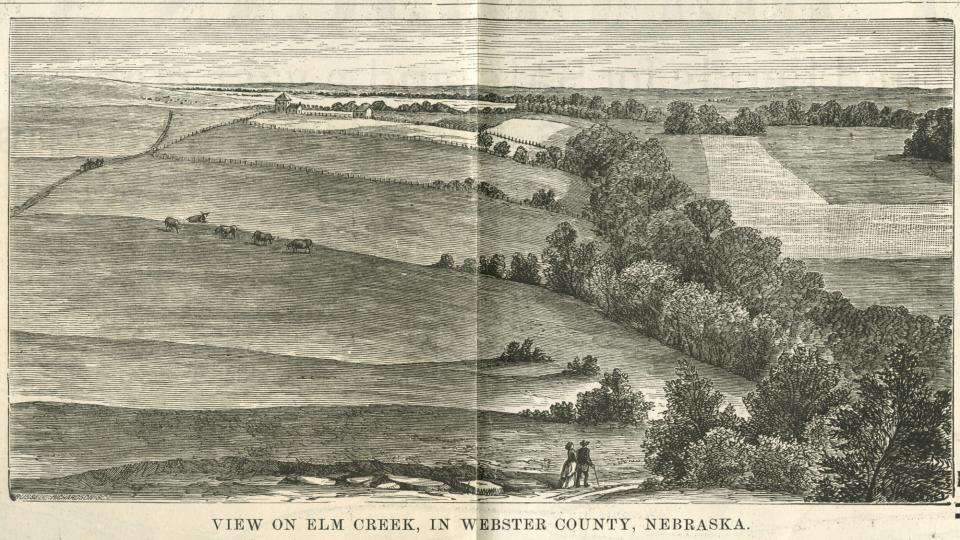

Detail from map of B. & M.Railroad Lands: View of Elm Creek in Webster County, Nebraska, 1880.

Detail from map of B. & M.Railroad Lands: View of Elm Creek in Webster County, Nebraska, 1880.

Courtesy of Newberry Library. CB&Q 769.8.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The back of the land grant maps contained relevant information on local climate, soils, successful crops and illustrations probably intended to entice and reassure potential settlers as well as inform them. This scene shows a gentle pastoral landscape, and seems to invite the viewer to see the land from the eyes of a couple surveying their domain.

Back of Columbus District map showing Elkhorn Valley at Oakdale, Antelope County, 1880.

Back of Columbus District map showing Elkhorn Valley at Oakdale, Antelope County, 1880.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q 769.8.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

While the Burlington had no incentive to deceive potential settlers, the text surrounding this scene suggests that they were not above putting the best possible spin on their land: “It is a pleasure to break the wild prairie, for there are no obstructions in the way of the happy plowman.” The horseman in the illustration seems relaxed as he easily herds his healthy cattle. The orderliness of the scene suggests that the fire in the background is a controlled fire, perhaps to prepare the ground for plowing. Wildfires, often set by cinders from the stacks of steam engines, were common in some regions, and a profound force in vegetation change.