Portrait of Jakob Gråberg af Hemsö.

Portrait of Jakob Gråberg af Hemsö.

Unknown artist, n.d.

Originally published in Frithiof Heurlin, Viktor Millqvist, and Olof Rubenson, Svenskt biografiskt handlexikon,1906.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In 1818–20 an outbreak of plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, swept over the Sultanate of Morocco. Although the country had been opened to European trade in the mid-eighteenth century, Morocco was still an agrarian society made up of isolated local communities. The foreign consuls in Tangier generally barred their doors and shuttered their windows to wait out the crisis and avoid infection, some taking refuge in country houses outside of the city. However, the Swedish acting consul and aspiring academic Jakob Gråberg af Hemsö (1776–1847) chose instead to seek knowledge amidst the crisis. His reports written during the ongoing plague epidemic and the publications that followed them offer us insights into early nineteenth-century epidemiology and the circulation of knowledge in the interplay between Europe and North Africa.

In June of 1819, after the worst of the ongoing epidemic had passed through Tangier, the plague returned to the city with an average daily death toll of 2–3 people. At this time Jakob Gråberg took the chance to inform the Swedish Health Collegium, the Cabinet for Foreign Correspondence, and the Quarantine Commissions in Gothenburg and Kristiansand of the latest medical developments he had observed. In a report to the Health Collegium dated 19 October 1819, Gråberg argued that as the government and inhabitants of Morocco saw no value in trying to contain the plague, there was “scarcely a better country” for studying the development and effects of the illness.

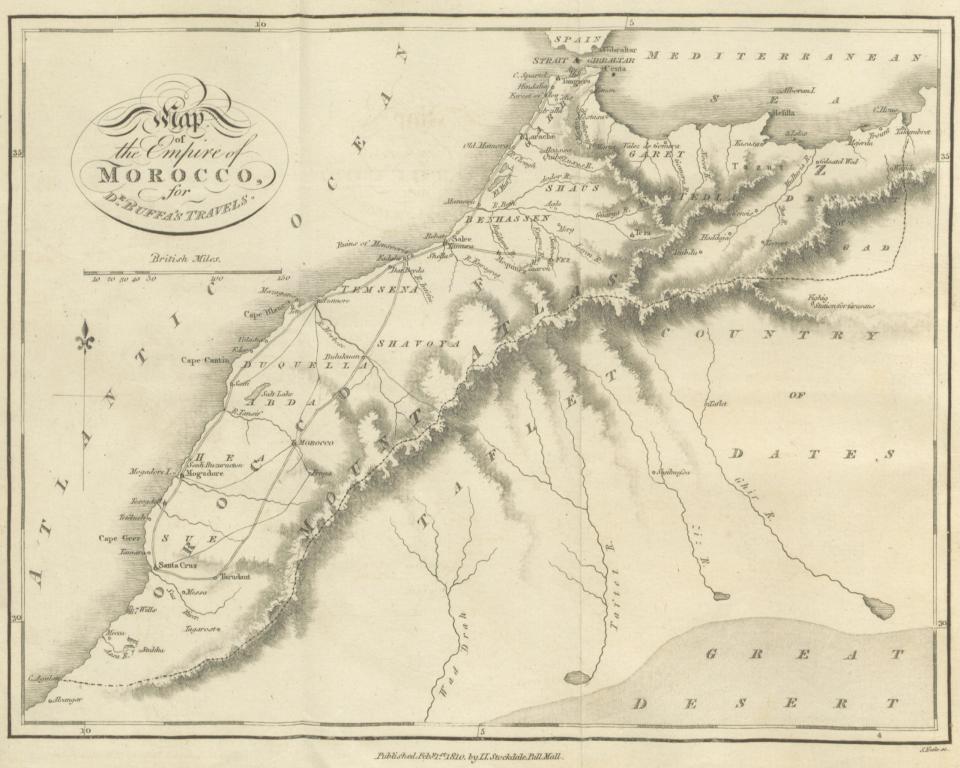

Map of Morocco in the early nineteenth century.

Map of Morocco in the early nineteenth century.

taken from “Travels through the Empire of Morocco” by John Buffa (1810). Public domain.

Originally published in John Buffa, Travels through the Empire of Morocco (London: J. J. Stockdale, 1810).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Title page of Jakob Gråberg’s work on the Empire of Morocco, including a list of cities in which he belonged to scientific societies. 1834.

Title page of Jakob Gråberg’s work on the Empire of Morocco, including a list of cities in which he belonged to scientific societies. 1834.

Courtesy of Oxford University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Gråberg’s first matter of interest was a cure utilized by the Portuguese consul to Morocco, José Januário Colaço. This treatment was based on the use of olive oil, which was to be both imbibed by the patients and rubbed on their skin. It is uncertain where this treatment first came into use, but it is mentioned by James Grey Jackson in his book An Account of the Empire of Morocco (1809) as being used in Morocco during the plague epidemic of 1799–1800. Jackson attributes the remedy to a late British consul to Egypt, George Baldwin (1744–1826), but the olive oil treatment could potentially be traced much further back in time. In a report to the Quarantine Commission of Gothenburg dated 1 June 1819, Gråberg noted that a great number of people in Tangier had been cured through this regimen—out of 300 patients treated, merely 12 had died. In a later report to the Health Collegium dated 10 August 1819, Gråberg described an attempt at inoculation against the illness. This procedure, performed by the Spanish physician Don Serafino Sola on a group of 17 Spanish deserters, was performed through the introduction of a mixture of diseased pus and olive oil into incisions made on the subjects. The experiment was apparently a success, with all subjects not only recovering from the mild bouts of plague brought on by the inoculation but also showing no signs of being re-infected afterwards. The contents of Gråberg’s reports on Colaço’s and Sola’s treatments were published in several Swedish newspapers and gained international attention in The Times, Annali universali di medicina, and Gazette de santé.

In his report to the Health Collegium of 10 August 1819, Gråberg presented a list of observations regarding the plague. These include his assertion that the plague did not spread through the air, but only through contact with diseased individuals or materials, which in turn allowed tiny, animal-like beings to make their way through the pores of the skin and cause the outbreak of the disease in the infected person. Because these minuscule beings needed air to breathe, he reasoned, a generous rubbing of olive oil asphyxiated them and halted the onset of plague. Gråberg attributed his understanding of this mechanic of infection to his study of the texts of several physicians and natural scientists: Lucretius, Vitruvius, Athanasius Kircher, Antonio Vallisneri, Erasmus Darwin, and Giovanni Rasori.

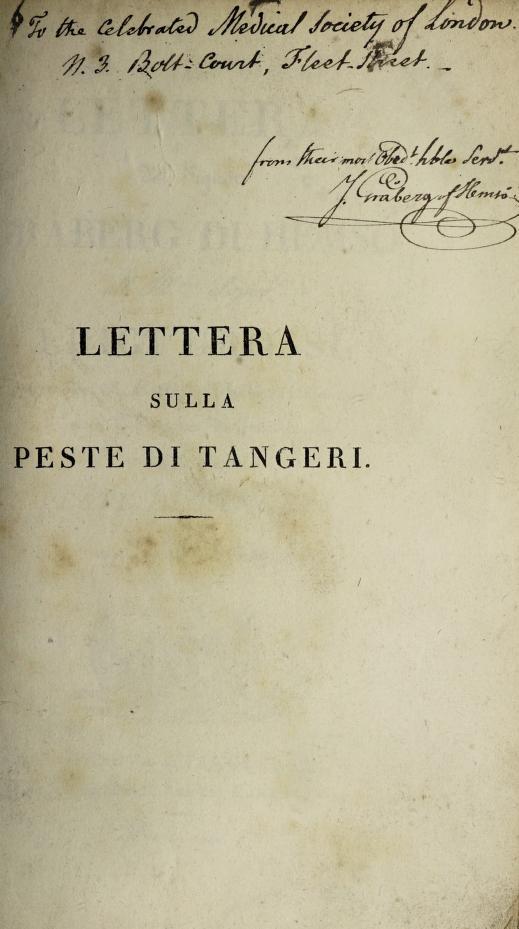

Cover page of the publication that Jakob Gråberg sent to the Medical Society of London. Note the author’s handwriting at the top. 1820.

Cover page of the publication that Jakob Gråberg sent to the Medical Society of London. Note the author’s handwriting at the top. 1820.

Courtesy of Open Library (openlibrary.org).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In a report to the Foreign Minister Lars von Engeström (1746–1826) of the same date, Gråberg intimated that it would be most gratifying to him if his notes on the plague would be presented at one of the meetings of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Further, Gråberg recommended that Don Serafino Sola should be considered for induction into the Health Collegium. Despite these suggestions, Gråberg’s findings were apparently not discussed at the meetings of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, nor were they ever published by that society. A possible reason may have been that Gråberg appears to have been considered a middling writer, described by his contemporaries as possessing more eagerness than skill. In his The Moorish Empire, published in 1889, Budgett Meakin criticizes Gråberg’s most well-known work, Specchio geografico, e statistico dell’Impero di Marocco (1834), calling it “over-rated” and pointing out its inaccuracies and outdated claims.

Although his writings were not always enthusiastically received by his contemporaries in his native country, Gråberg was very active in communicating his research to the international scientific community of the early nineteenth century. His letters to the Genovese physician Luigi Grossi on the topic of the plague in Tangier were printed in Genoa in 1820. Gråberg sent copies of this publication to the Medical Society of London, and presumably to other scientific societies of which he was a member. The reach of Gråberg’s texts illustrates the developing connectedness of early nineteenth century science and the role that geographically isolated individuals played in communicating new developments.

How to cite

Kaukonen, Emil. “Science in the Time of the Plague: Jakob Gråberg and the Moroccan Plague Epidemic of 1818–20.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2020), no. 38. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9132.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Emil Kaukonen

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- El Mansour, Mohamed. Morocco in the Reign of Mawlay Sulayman. Wisbech: Middle East & North African Studies Press, 1990.

- Gråberg af Hemsö, Jakob. Lettera del signore Gråberg di Hemsö all'illmo signor Luigi Grossi sulla peste di Tangeri negli anni 1818–19. Genova and Tangiers: Antonio Ponthenier, 1820.

- Gråberg af Hemsö, Jakob. Specchio geografico, e statistico dell’Impero di Marocco. Genova: Dalla Tipografia Pellas, 1834.

- Meakin, Budgett. The Moorish Empire. London: Sonnenschein & Co., 1889.

- Roberts, Lissa. “Situating Science in Global History: Local Exchanges and Networks of Circulation.” Itinerario 33, no. 1 (2009): 9–30.

- Stearns, Justin K. Infectious Ideas: Contagion in Premodern Islamic and Christian Thought in the Western Mediterranean. Baltimore: JHU Press, 2011.

- Zetterstéen, Karl Vilhelm. Jakob Gråberg af Hemsö som arabist. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1949.